Deepfake technology is one of the most fascinating and unsettling developments in artificial intelligence. It allows anyone to create hyper-realistic videos or audio that mimic real people. On one hand, it opens the door for creative innovation in entertainment, education, and art. On the other hand, it poses severe risks when misused for fraud, political manipulation, or exploitation.

So, how do we balance innovation with ethical responsibility? Let’s dive into both sides of the debate.

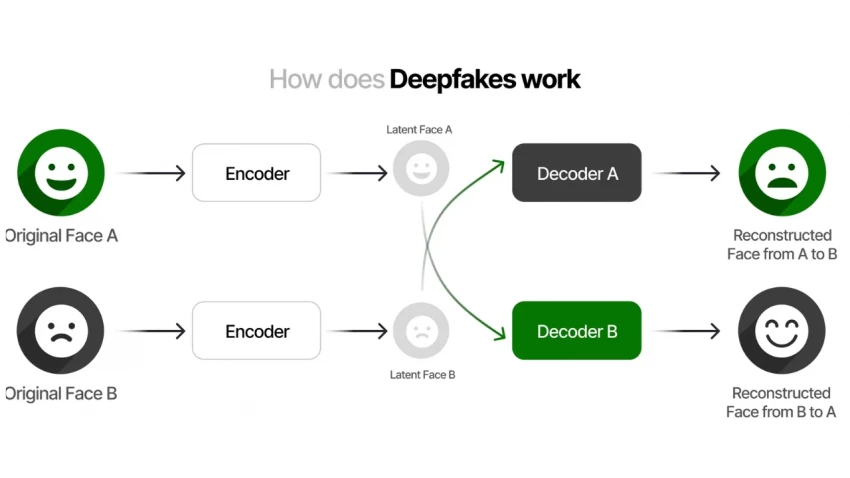

Deepfakes use generative adversarial networks (GANs) to swap or synthesize faces, voices, or entire bodies in video or audio recordings. A generator creates fake images, while a discriminator evaluates them against real ones until the output becomes nearly indistinguishable from reality.

By 2020, experts estimated that over 96,000 deepfake videos were circulating online, a figure that has since grown exponentially with tools like DeepFaceLab, FaceSwap, and AI voice clones becoming publicly accessible.

Could deepfakes be a force for good? The answer is yes, in controlled and transparent settings.

Hollywood already uses deepfake technology to resurrect deceased actors or de-age characters. For example, “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” digitally recreated Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin. Instead of CGI costing millions, deepfakes can produce similar results at a fraction of the price.

Imagine historical figures teaching history lessons or an AI-generated Albert Einstein explaining relativity in simple terms. Deepfakes could bring learning to life in ways textbooks never could. They can also make lectures accessible by generating real-time translations and lip-sync adjustments.

Satirists and artists use deepfakes to push boundaries of comedy, commentary, and cultural critique. As with political cartoons, deepfakes can serve as social commentary when audiences understand they are fictional.

For all its promise, deepfake technology comes with alarming risks.

One of the most dangerous uses of deepfakes is in politics. Imagine a fake video of a world leader declaring war or conceding defeat in an election. A 2020 MIT study found that deepfakes, when weaponized, could undermine trust in democratic institutions and spread chaos faster than fact-checkers can respond.

A disturbing 96% of online deepfake videos are pornographic, with the vast majority targeting women without their consent. This raises urgent questions about privacy, consent, and digital abuse.

Deepfake voices have already been used in scams. In 2019, criminals used an AI-generated voice to impersonate a CEO, tricking a UK-based company into transferring $243,000.

So, should deepfakes be banned or embraced? The answer lies somewhere in the middle.

Ethically, the main issue is consent and intent. If someone uses deepfakes for art, parody, or education with clear disclosure, the benefits outweigh the risks. But when used to deceive, exploit, or manipulate, they cross into dangerous ethical territory.

This brings us to two questions:

Some countries have already begun addressing the risks.

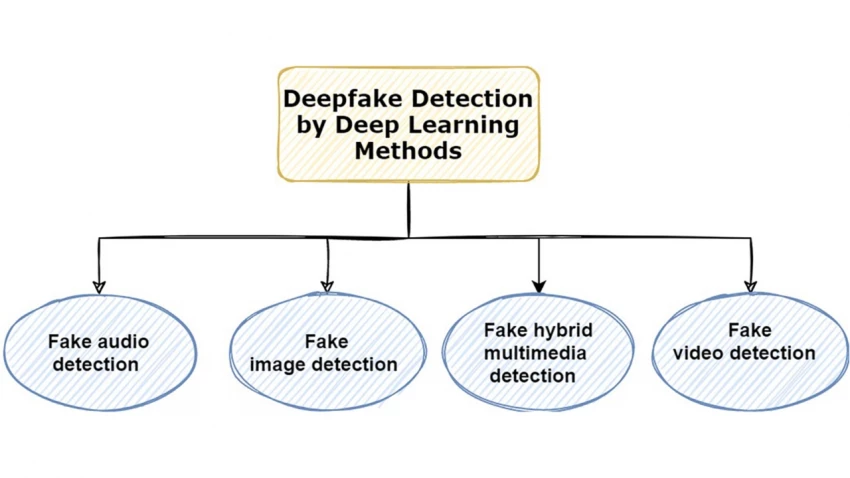

Meanwhile, platforms like Twitter and Meta now remove manipulated media that could cause harm. But detection remains difficult; AI tools that identify deepfakes often lag behind new generative techniques.

To move forward, we need a three-pronged approach:

Much like Photoshop in the 2000s, deepfakes will eventually become a normalized creative tool. The challenge lies in ensuring that normalization doesn’t erode truth itself.

Deepfake technology sits at the intersection of creativity and deception. It can make films more immersive, education more engaging, and art more innovative. But it also threatens democracy, privacy, and trust.

The ethical path forward requires transparency, regulation, and public awareness. Deepfakes themselves are not inherently evil; it’s the intent behind them that determines whether they inspire or deceive.

So the real question is: Do we, as a society, have the wisdom to use deepfake technology responsibly?

Be the first to post comment!