Tips & Tricks

6 min read

The Lost Art of Bookbinding: When Books Were Works of Art

Before machines took over, getting a new book was a special experience.

You didn’t just pick one up from a shelf or order it online. Instead, you waited—sometimes for weeks or even months—while a skilled artisan carefully put it together by hand.

When you finally got your hands on a hand-bound book, you could feel the difference.

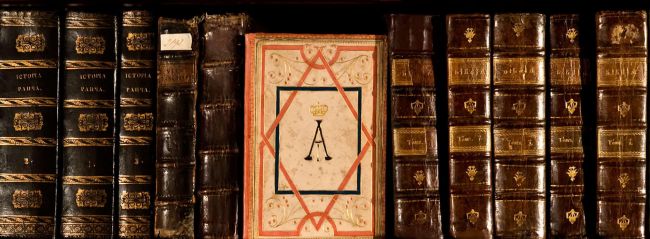

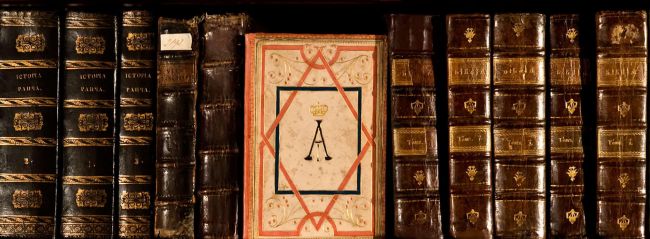

It wasn’t just paper and ink. The book had weight and presence. The stitching was neat and strong, so you knew it would last. The covers were made from fine calfskin or beautifully embossed cloth, giving each book a unique look and feel.

You noticed the little details:

The spine often had gold leaf titles or symbols that meant something—maybe to your family, your city, or your school. Some covers even had paintings, metal inlays, or jewels. These touches made the book feel even more special.

Owning a hand-bound book was about more than just reading.

It was something to show off, to pass down to your children, and to treasure. The book itself told a story before you even opened it. Its weight, its smell, and its look all reminded you that it was made with care and meant to last.

If you’ve ever held a book like this, you know it feels different.

It’s not just a story inside—it’s a piece of art you can hold in your hands. And if you’re curious about how books are made, you might be inspired to try bookbinding yourself. It’s a way to connect with a tradition that’s all about patience, skill, and love for the craft.

Every era shaped how books were bound in its own way.

In medieval times, monks worked on sacred texts, carefully attaching clasps, hinges, and sometimes even chains to keep books safe. These books were heavy, designed for stone shelves and the dim glow of candlelight.

Later, during the Renaissance, bookbinding became lighter and more colorful. Beautiful marbled papers started to appear inside the covers and on the endpapers. Binders began adding initials or symbols, making each book more personal.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, bookbinding really took off as more people learned to read and libraries grew. New designs began to emerge. French bindings were known for their elegance, while English bindings stood out for their precision. Owners often asked for custom covers featuring family crests or favorite flowers. Some books even had secret compartments or pages painted so that an image would only appear when the pages were fanned out. Every little detail had a purpose, and every stitch had meaning.

Certain choices made the bound book unforgettable. The texture of leather is rough or soft. The scent of handmade glue and paper. The creak of a tight spine opening for the first time. Each book came with its own character shaped by human hands and thoughtful eyes.

This devotion to detail carried meaning beyond function. It was about pride. A well-bound book could last for generations, crossing borders and oceans, holding memories as tightly as it held its pages. Some bindings even outlived the words inside, becoming prized objects on their own. A lost novel might fade from public memory, but its cover might still sit in a museum case, admired for its artistry.

To understand what made this craft so unique, consider these often overlooked elements:

1. Hand-Tooled Leather Covers

Imagine:

A bookbinder uses hot metal tools to press beautiful patterns into soft leather covers. Each design is carefully planned and done by hand—there’s no “undo” button! Sometimes, thin sheets of gold are added to the cover to make it shine. It can take days just to finish one cover. Over time, the leather gets softer and more beautiful with every touch.

2. Sewn Spines with Linen Thread

How it’s different:

Today, most books are glued together. But in the past, binders used strong linen thread to sew the pages together. This made the book tough, it could withstand rough use, travel, and even adverse weather conditions. You could see the stitching inside, a reminder of the hard work that went into making it. These books could bend without breaking, lasting for generations.

3. Hand-Colored Edges and Marbled Endpapers

What makes it special:

The edges of the pages weren’t just plain, they were often dyed in rich colors like red, blue, or green. Sometimes, the inside covers had “marbled” paper, made by floating ink on water and pressing paper onto it. Every marbled pattern was unique, giving each book its own look. These touches weren’t just pretty, they showed that the book was made with care and meant to be treasured.

All these little things gave hand-bound books a special “soul.” Every mark, color, or stitch told a story about the person who made it. Even small mistakes made the book feel more real and alive. As the book aged, it became even more beautiful, carrying its history with pride.

In short:

Traditional bookbinding was about craftsmanship, patience, and attention to detail—making each book not just a thing to read, but a work of art to cherish.

While most books today come from machines, echoes of traditional binding still survive. Independent bookbinders and small studios continue the work, often blending old techniques with modern themes. They make books for weddings, anniversaries, poetry collections, and limited runs. Artists bind zines by hand, sew sketchbooks, add wood covers, and carve patterns with brass tools. Some even use materials like denim or felt to give each object a new voice.

Z library brings together resources found across Project Gutenberg and Open Library, preserving not only stories but also the spirit of old bindings through scanned pages that often show marginalia, torn edges, or signs of use. These marks speak to the past as clearly as any ornate cover ever did.

The care once given to each book may seem rare now, but its legacy remains. The old binders left behind not only volumes but a standard. They proved that a book could be both vessel and vision. Something to hold and something to behold.

Be the first to post comment!