India’s 3nm Semiconductor Ambition: A Decade-Long Leap From 28nm to the Global Frontier

by Suraj Malik - 1 week ago - 4 min read

India has set one of the most ambitious semiconductor goals in the world: building 3-nanometre (3nm) chips by 2032. If achieved, the milestone would place the country among an elite group of semiconductor powers currently dominated by Taiwan and South Korea. Yet the path from ambition to execution remains steep, technically complex, and historically unprecedented.

For decades, India remained largely absent from mainstream chip manufacturing despite early efforts such as the Semiconductor Complex in Mohali and intermittent interest from global firms. That began to change after the Covid-19 pandemic exposed global chip supply vulnerabilities, pushing semiconductors into the realm of national strategy.

The turning point came in December 2021, when the Indian government launched the ₹76,000-crore Semicon India programme, aiming to build domestic manufacturing, packaging, and design capabilities. Since then, the policy ambition has sharpened dramatically.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Electronics and IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw publicly laid out India’s roadmap: 7nm chips by 2030 and 3nm by 2032—a compressed timeline that typically spans several decades even for established semiconductor leaders.

Where India Stands Today

As of early 2026, India has moved decisively from policy announcements to physical construction, though only at mature process nodes.

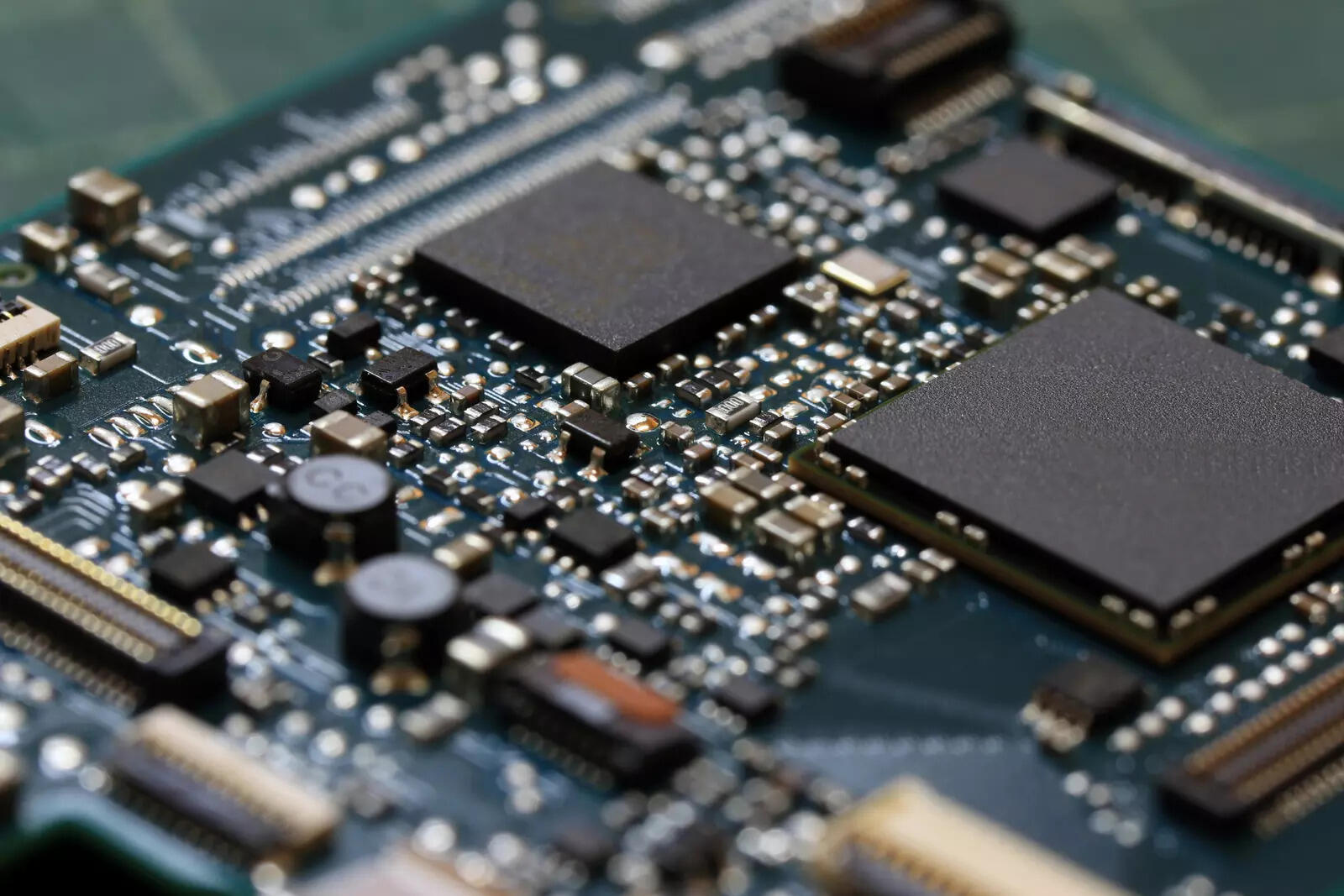

The country’s first commercial front-end fab—led by Tata Electronics in partnership with Taiwan’s PSMC—is under construction in Dholera, Gujarat. The ₹91,000-crore facility will begin production at 28nm, with trial runs targeted for 2027 and a full capacity of up to 50,000 wafers per month.

Alongside this, several back-end packaging and testing projects have been approved. Micron Technology is building a memory assembly and test facility expected to become operational in 2026, while CG Semi and Kaynes Semicon are setting up advanced packaging lines.

Global equipment suppliers are also committing capital. Applied Materials is investing $400 million in an engineering centre in Bengaluru, while Lam Research has announced plans to invest roughly ₹10,000 crore in India.

Together, these moves signal that India’s semiconductor “build phase” has clearly begun—but only at nodes far from the leading edge.

Why 3nm Is a Different Universe

The leap from 28nm to 3nm is not incremental—it is transformative. At 3nm, chips pack billions of transistors into areas smaller than a fingernail, enabling the high-performance processors that power smartphones, data centres, and artificial intelligence workloads.

Globally, only TSMC and Samsung Electronics manufacture 3nm chips in volume. Even Intel, long a semiconductor leader, has struggled to stabilise its most advanced nodes.

Experts identify three core barriers for India: equipment, yields, and talent.

First, 3nm manufacturing requires Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, supplied almost exclusively by ASML. Each EUV machine costs up to $200 million, takes more than a year to build, and is subject to strict export controls, making access a strategic issue rather than a simple purchase.

Second, yields at 3nm are unforgiving. Even microscopic defects can destroy entire chips, meaning years of iterative learning are required before production becomes commercially viable.

Third, while India has world-class chip design talent, it lacks a deep pool of engineers with hands-on experience running advanced fabs. Recruiting experienced global talent—particularly from the Indian diaspora—will be essential but challenging.

Can India Compress Decades Into Ten Years?

The government’s timeline implies moving from 28nm to 3nm in less than a decade. Industry veterans caution against skipping intermediate nodes such as 22nm, 14nm, and 7nm, which serve as critical learning platforms for yield engineering and process control.

History offers sobering lessons. TSMC took decades to reach 3nm, and even then required roughly three years to move from 5nm to stable high-volume 3nm production. Samsung faced yield challenges at 3nm despite its experience, while Intel’s struggles show that access to equipment alone does not guarantee success.

Ambition Meets Reality

India’s semiconductor push is no longer theoretical. Fabs are being built, packaging lines approved, and global suppliers are investing real capital. At the same time, 3nm represents one of the hardest industrial challenges on earth—technically, financially, and geopolitically.

The most realistic measure of success may not be whether India produces 3nm chips exactly by 2032, but whether it builds a continuous, self-sustaining semiconductor ecosystem—from design to manufacturing to packaging—without repeating the false starts of the past.