Physical Intelligence Wants to Build the “ChatGPT for Robots” — and Investors Are Funding It Without a Revenue Plan

by Suraj Malik - 1 week ago - 4 min read

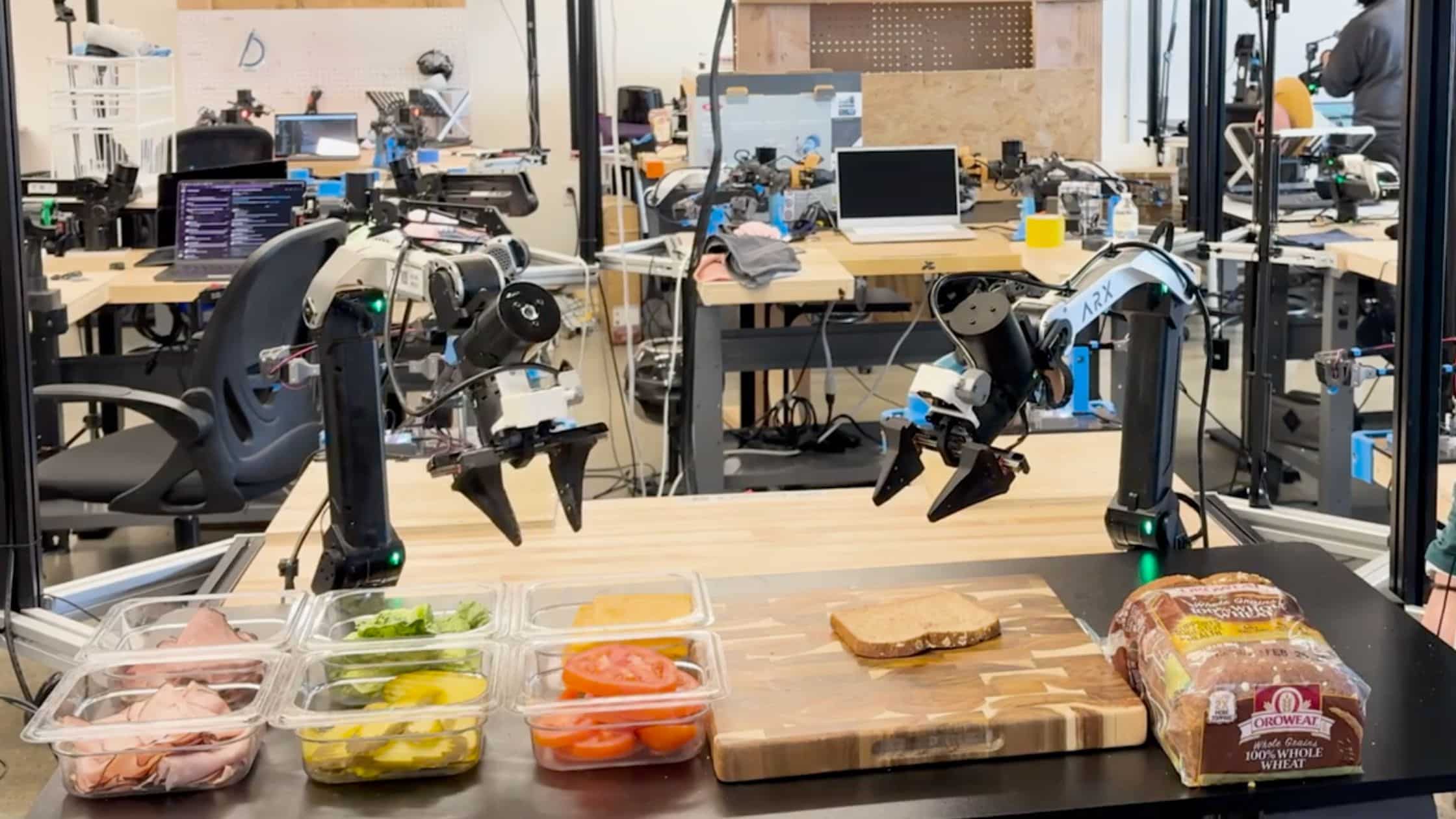

In a quiet San Francisco warehouse marked only by a subtle π symbol on the door, dozens of low-cost robotic arms are practicing tasks that look unimpressive—until you realize what they’re meant to represent: a new kind of foundation model designed to make robots broadly useful across many environments, not just one factory line.

That’s the bet behind Physical Intelligence, a two-year-old startup that has raised over $1 billion, is valued at $5.6 billion, and—unusually for a company at that valuation—offers investors no clear commercialization timeline.

Its co-founder Lachy Groom, a former early Stripe employee and later prolific angel investor, says the company’s focus is research first, built around the idea that general robotic intelligence is a multi-year infrastructure problem rather than a product sprint.

“ChatGPT, but for Robots”

One of the company’s co-founders, Sergey Levine, describes the ambition plainly: “Think of it like ChatGPT, but for robots.”

At headquarters, the approach is visible in the daily loop: robots attempt everyday manipulation tasks—folding pants, turning a shirt inside out, peeling vegetables—while the team collects data from internal stations and external settings like warehouses and homes. That data trains general-purpose robotic models, which are then tested again in the lab.

Even the espresso machine in the building isn’t for staff—it’s there so robots can learn from repeated interaction. “Foamed lattes are data,” not a perk.

Cheap Hardware, Expensive Compute

Physical Intelligence is deliberately using off-the-shelf robotic arms that sell for around $3,500, because the company believes “good intelligence compensates for bad hardware.” Levine notes that if manufactured in-house, the materials cost could drop below $1,000—an argument for scaling capability through software rather than high-end mechanics.

On spending, Groom says the company doesn’t “burn that much” relative to its funding—because most of the cost goes into compute. He’s also blunt about what additional money would buy: “There’s always more compute you can throw at the problem.”

Backers named in the report include Khosla Ventures, Sequoia Capital, and Thrive Capital.

The Strategy: Cross-Embodiment Learning

A core technical claim from the team is that their models can learn in a way that transfers across different robot “bodies.”

Co-founder Quan Vuong says the long-term goal is reducing the cost of bringing autonomy to new robot platforms—so if a company builds new hardware tomorrow, it won’t need to start data collection from scratch. “The marginal cost of onboarding autonomy… is just a lot lower,” he argues.

The startup is already testing its systems with a small number of companies across verticals—logistics, grocery, and even a chocolate maker nearby—suggesting it’s exploring real-world readiness without formally positioning itself as a commercial robotics vendor yet.

A Rival With the Opposite Playbook: Skild AI

Physical Intelligence’s research-first stance stands out even more because of what’s happening elsewhere in the market.

Skild AI—based in Pittsburgh—recently raised $1.4 billion at a reported $14 billion valuation, and says it has already deployed its “omni-bodied” system commercially, generating $30 million in revenue in a few months across security, warehouses, and manufacturing.

Skild has also publicly criticized what it describes as “robotics foundation models” that resemble vision-language models without “true physical common sense,” arguing for approaches grounded in physics-based simulation and real robotics data.

In short: Skild is betting on deployment-driven data flywheels, while Physical Intelligence is betting that resisting near-term product pressure produces better general intelligence—a divide that may take years to settle.

A $5.6B Company With No Timeline — by Design

What makes Physical Intelligence unusual isn’t just its ambition—it’s the structure of the bet. Groom says he doesn’t give investors “answers on commercialization,” acknowledging it’s “a weird thing” that people tolerate, but one that also explains why the company wants to be well-capitalized early.

For now, the company reportedly has about 80 employees and plans to grow—“as slowly as possible,” Groom says—while wrestling with the realities of robotics: hardware breaks, arrives slowly, and complicates testing and safety in ways software startups don’t face.

Meanwhile, the robots keep practicing—pants still not perfectly folded, shirts still stubbornly right-side-out, zucchini shavings steadily piling up.

The bigger question isn’t whether those tasks will eventually work. It’s whether building the “ChatGPT for robots” requires years of insulated research—or whether the fastest path to intelligence is getting imperfect robots into the real world as soon as possible.