Technology Is Now a Pillar of National Power, IBM CEO Tells World Leaders in Dubai

by Vivek Gupta - 3 days ago - 5 min read

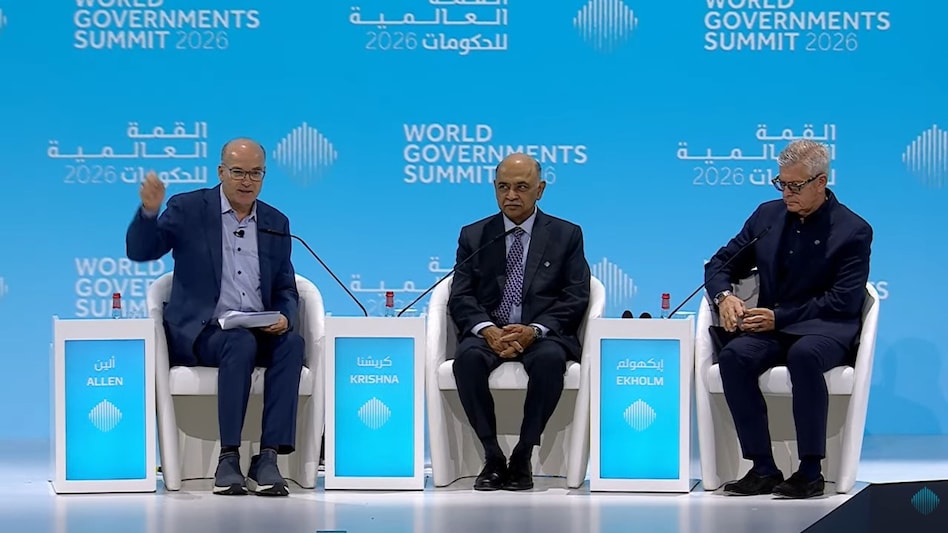

At this year’s World Governments Summit in Dubai, a familiar conversation about innovation took on a sharper edge. Technology, IBM chief executive Arvind Krishna argued, is no longer just an economic accelerator or productivity tool. It now sits alongside defense and finance as a core pillar of national power.

Speaking on February 3, 2026, at the annual gathering of global policymakers, Krishna framed technology as a “force multiplier” that amplifies the effectiveness of everything from military capability to financial systems and public services. The remark landed in a room that included more than 35 heads of state, hundreds of ministers, and senior executives from the world’s largest technology firms.

The statement reflects a broader shift underway in how governments think about power, resilience, and competitiveness in an era defined by artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and geopolitically fragile supply chains.

A Summit Focused on Power, Not Just Progress

The World Governments Summit has long been a venue for ambitious ideas, but the 2026 edition carried a distinctly strategic tone. With more than 6,000 attendees from 150 countries, discussions repeatedly returned to one theme: control.

Krishna’s argument was blunt. Defense preserves sovereignty. Finance enables investment. Technology, he said, multiplies the impact of both. Countries that fail to treat technology as strategic infrastructure risk falling behind across every domain, from healthcare and logistics to national security.

That framing resonated with governments grappling with AI dependence, semiconductor shortages, and growing concern over who controls critical digital systems.

Sovereignty Without Isolation

Krishna was careful to avoid endorsing full technological self-sufficiency. Instead, he outlined a pragmatic middle path. Governments, he said, must retain direct control over critical systems such as defense networks, financial infrastructure, and sensitive data platforms. Beyond that, partnerships remain essential.

“It’s not exclusive,” Krishna noted, arguing that total independence is neither realistic nor efficient. The priority, in his view, is ensuring that no external actor can switch off, compromise, or misuse systems that underpin a nation’s stability.

This approach stood in contrast to a more skeptical view presented on the same panel by Börje Ekholm, chief executive of Ericsson. Ekholm challenged the very idea of tech sovereignty, warning that it creates a false sense of independence.

The Case for “Trusted Interdependence”

Ekholm’s counterargument was rooted in practical reality. Even the world’s largest economies, he said, rely on foreign technology at multiple layers of their digital stack. The United States depends on European telecom infrastructure. Europe relies on American cloud platforms. No nation operates in isolation.

Rather than sovereignty, Ekholm advocated what he called “trusted interdependence,” a model in which countries diversify suppliers, build redundancy, and choose partners carefully instead of attempting to own every layer themselves. The goal is resilience, not self-containment.

The exchange highlighted a tension governments increasingly face: how to balance control with collaboration in systems that are inherently global.

Quantum Moves From Theory to Strategy

Beyond geopolitics, Krishna pointed to a near-term technological inflection point: quantum computing. Once treated as distant science, quantum systems are now entering an engineering phase, he said, with commercial advantages expected within two to three years.

IBM’s roadmap places the first verified quantum advantage as early as 2026, followed by practical applications in materials science, finance, and optimization later in the decade. By 2029, Krishna said, fault-tolerant quantum systems could fundamentally change how certain problems are solved.

For governments, this timeline matters. Quantum capability is no longer a long-term research bet but a strategic asset with implications for national competitiveness, cryptography, and industrial leadership.

AI’s Two-Track Future

Krishna also pushed back on the idea that the AI race is only about who builds the largest foundation models. Large models will matter, he said, but smaller, domain-specific systems will do most of the work in real economies.

That distinction opens the door for countries without hyperscale infrastructure to compete by focusing on applied AI in chemistry, manufacturing, energy, and physical infrastructure. In Krishna’s telling, AI advantage will be distributed, not monopolized.

Networks Built Around Intelligence

The discussion extended into the next generation of connectivity. Ekholm outlined a vision for 6G networks, expected around 2030, that are AI-native by design. Unlike 5G, where AI optimizes performance at the edges, 6G would embed learning and reasoning into every layer of the network.

The result, he argued, would be intent-based connectivity. Applications would declare what they need, and the network would configure itself automatically. In such a world, connectivity becomes invisible infrastructure, adapting in real time to demand.

Why Governments Are Listening

The urgency of the debate reflects recent shocks. Wars, trade restrictions, and AI-driven supply shortages have exposed how dependent national systems are on technology decisions made elsewhere. Data localization laws, export controls, and sovereign AI initiatives are all symptoms of that realization.

The takeaway from Dubai was not that governments must choose between openness and control, but that technology governance has become statecraft. Decisions about cloud platforms, AI models, and networks now shape economic resilience and national security as much as traditional policy tools.

As one theme echoed through the summit halls, it was this: technology is no longer an enabler on the sidelines. It is a strategic instrument. And governments that fail to treat it as such may find themselves negotiating from a position of weakness in the decade ahead.