ChatGPT Ghibli art is the viral wave of AI-generated images that re-imagine selfies, family photos, memes, and everyday scenes in a dreamy Studio Ghibli–style aesthetic. It matters because it sits at the center of three major conversations at once: fan culture, generative AI creativity, and the ethics of imitating a beloved studio’s visual identity with a single prompt.

Across social platforms, these images have become instantly recognizable soft, nostalgic, and emotionally comforting—while also sparking heated debates about authorship, consent, and artistic labor.

ChatGPT Ghibli art refers to AI-generated images that apply a hand-painted, pastel, whimsical look reminiscent of films by Studio Ghibli to ordinary photos or text prompts.

With recent multimodal updates to ChatGPT, users can upload an image or type prompts such as “turn this into Studio Ghibli style” and receive convincing results within seconds. This ease of use helped the trend spread rapidly across platforms like X, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube.

What makes this moment significant is not just the quality of the images, but the fact that a general-purpose AI system can now mimic a globally recognizable artistic identity with minimal effort. That capability raises questions about copyright, consent, and whether a visual style can—or should—be absorbed into a model.

At the same time, it gives non-artists a way to visually “step into” the kinds of worlds they grew up watching, which explains the trend’s strong emotional pull and shareability.

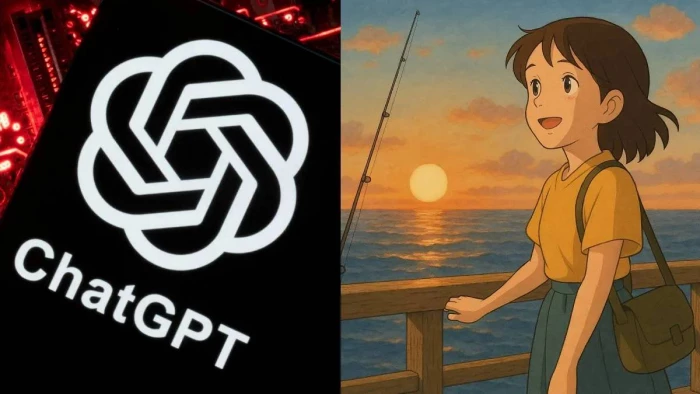

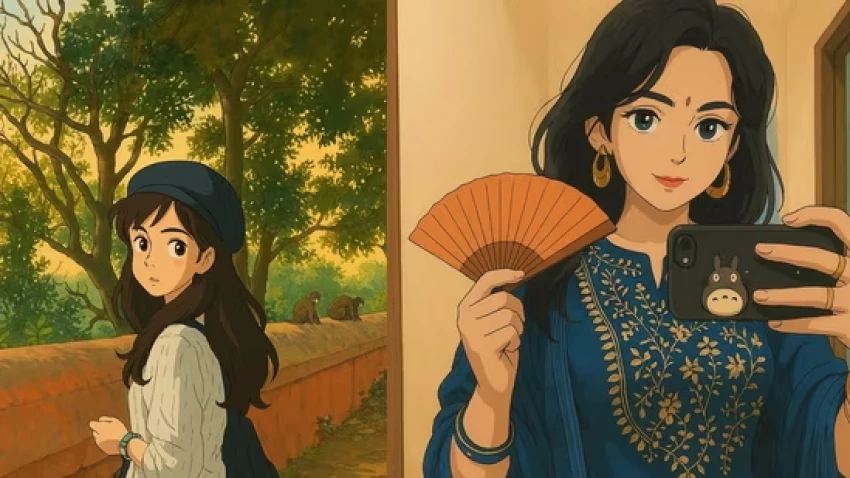

After reviewing dozens of viral posts and compilation threads across social media, a clear pattern emerges: people are using Ghibli-style AI art to reframe ordinary life as something gentler and more magical.

Common formats include:

● “What if my city was in a Ghibli movie?”

● Ghibli-style wedding or childhood photos

● Pets, homes, and travel scenes rendered in soft anime tones

The images feel nostalgic, wholesome, and idealized—qualities that perform extremely well in algorithm-driven feeds. Because the process requires no drawing skill, it lowers the barrier to creative participation and turns a complex animation aesthetic into a casual, shareable meme format.

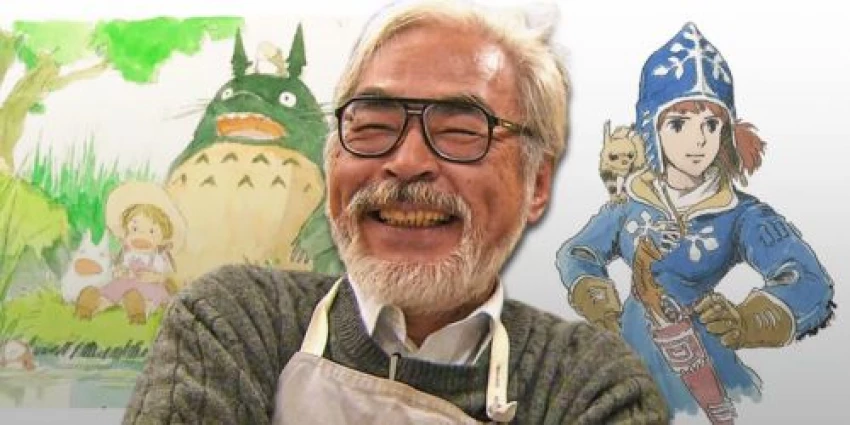

Founded in the 1980s by Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and Toshio Suzuki, Studio Ghibli defined a distinctive visual language built on soft color palettes, meticulous backgrounds, and emotionally rich character animation.

Films such as Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro shaped generations of animators and audiences alike. Over time, “Ghibli-style” became shorthand for a specific blend of warmth, nostalgia, and magical realism in 2D animation.

Crucially, Ghibli’s films are also deeply personal and hand-crafted. Miyazaki has repeatedly emphasized pain, empathy, and lived experience as the foundation of his work. That context explains why his past criticism of AI-generated animation—calling it “an insult to life itself”—has resurfaced during the ChatGPT Ghibli art trend. For many artists, the current wave of AI images feels like decades of labor and philosophy reduced to a reusable aesthetic template.

ChatGPT does not include an official “Ghibli filter.” Instead, it relies on natural-language prompts that trigger certain visual patterns learned during large-scale training.

Users discovered that combinations like “hand-drawn,” “soft watercolor,” “gentle lighting,” and “Studio Ghibli-style” reliably produce images that resemble the studio’s aesthetic. The typical workflow is simple:

1. Upload a photo or describe a scene

2. Ask ChatGPT to “Ghiblify” it

3. Refine the prompt with mood or lighting details

4. Share the result online

This simplicity is the appeal—and the controversy. What once required years of training can now be approximated in seconds, democratizing access to the style while also unsettling professional artists who spent their careers mastering it.

Social media timelines have been flooded with Ghibli-style portraits and scenes, often presented as playful “what if” scenarios. Many users describe the images as comforting or magical, and some adopt them as profile pictures, prints, or visual mood boards.

For non-artists, ChatGPT Ghibli art feels like a creative superpower. Educators and hobbyists also use it as an accessible way to explore visual storytelling and to introduce students to the language of animation aesthetics.

Many illustrators and animators argue that the trend is disrespectful. In artist forums and comment threads, a recurring concern is that years of hand-drawn craft are being flattened into a one-line prompt.

Critics also point to cases where Ghibli-style AI art has been used to depict sensitive political or historical events in a cozy, sanitized way, which they see as trivializing real suffering. Ethical concerns generally focus on three areas:

● Lack of consent from the original creators

● Use of Ghibli-style branding for clicks or monetization

● Fear that AI lookalikes will undercut human commissions

Some fans argue that genuinely honoring Ghibli means studying the work and creating original art, not outsourcing its look to a model trained on others’ labor.

Legally, most copyright systems protect specific works rather than styles. This places Ghibli-style AI images in a gray area unless they closely replicate particular characters, frames, or trademarks.

However, debates are intensifying around whether mass imitation of a highly distinctive style—especially when promoted as a selling point—should trigger new protections. Ethically, even when such outputs are lawful, critics argue that training on copyrighted work without permission and monetizing the results fails a basic fairness test.

When an AI model can churn out thousands of “Ghibli‑style” images on demand and that look is advertised as a product feature, it stops feeling like casual influence and starts looking like industrialized free‑riding on a studio’s visual identity. The style itself works almost like a brand: people recognise it instantly, and platforms use that recognition to attract users without any relationship to the original creators.

Because copyright was designed to protect specific works, not styles, this kind of mass imitation falls into a legal gap that older law never anticipated, which is why scholars are now discussing ideas like limited “style rights” or using trademark‑style rules against misleading “in the style of X” marketing.

Critics focus on the pipeline: copyrighted artworks are scraped, ingested into training sets without permission, and then turned into paid products that directly compete with the markets those artists rely on (commissions, stock, covers). Even if some of this can be argued as lawful “fair use,” the economic reality is that the cost and risk sit with individual creators while the upside flows to a few large AI companies.

Policy reports and early decisions are starting to reflect this concern, stressing that when training leads to outputs that substitute for the original works, the “transformative” defense looks much weaker. That is why critics say it fails a basic fairness test: creators never got to say yes, and they rarely see attribution or revenue from systems built on their work.

Supporters point out that human artists have always learned by copying and remixing predecessors, from students reproducing Old Masters to modern filmmakers quoting classic shots. They argue that generative models are doing something analogous at scale: internalising patterns rather than storing full images, then producing new combinations rather than literal clones.

From this angle, trying to ban imitation outright would freeze the very process that makes art evolve; the more realistic target is how the ecosystem is governed: which data can be used, whether artists can opt out or license in, how money flows, and how AI‑made work is labelled.

Because “style” is hard to define in law and influence is core to creativity, many serious proposals now focus on conditions instead of trying to outlaw stylistic borrowing itself. These include licensing schemes for training datasets, collective bargaining bodies for artists, opt‑out/opt‑in registries, and clearer rules around using artist or studio names in marketing.

From a capabilities standpoint, AI already outperforms many humans in speed, stylistic range, and volume. For low-budget or high-volume illustration, this makes it highly competitive.

However, human artists contribute elements AI cannot replicate: lived experience, intentionality, and authorship. Miyazaki’s criticism captures this gap—what disturbed him was not just the output, but the absence of empathy behind it.

Art careers involve more than producing images. They require building a voice, negotiating meaning, and standing behind work when it is criticized or misused. AI tools can accelerate workflows or provide references, but they do not assume responsibility or agency.

In practice, the market is likely to restructure rather than collapse:

● Routine, low-margin content becomes increasingly automated

● High-end, narrative-driven, or deeply personal work emphasizes its human origin, with labels like “hand-drawn” or “no AI” becoming part of the value proposition

In the near term, Ghibli-style AI art is likely to remain a staple of social feeds. It combines nostalgia, low effort, and high shareability, and has already solidified into a recognizable meme format with hashtags like #StudioGhibliAI and Ghiblification.

Longer term, three forces will shape its future:

● Platform policies: AI companies are discussing tighter rules around imitating individual artists and clearer opt-out mechanisms

● Legal developments: Court cases around training data and consumer confusion may set new boundaries

● Community norms: A growing push for labeling AI outputs and celebrating hand-drawn fan art may become an informal standard

ChatGPT Ghibli art perfectly illustrates the double edge of generative AI. It gives ordinary people a playful way to enter a cherished visual universe, yet it leans heavily on the uncredited labor and emotional legacy of the artists who built that universe.

The healthiest path forward is not banning AI outright, but establishing clearer consent around training data, honest labeling of AI outputs, and economic models that allow artists to choose how their work is used while benefiting from new tools.

For users, a simple guideline helps: treat Ghibli-style AI art as fan-level play, not a substitute for real Ghibli or living artists. If a style matters enough to borrow, it matters enough to support the people who created it.

Be the first to post comment!