Inworld AI has been one of the more interesting tools experimented with recently for realtime characters and voice, but it is not a “magic bullet.” The platform shines when you lean into its strengths—voice quality, latency, and character depth—but it also comes with noticeable cost and complexity tradeoffs.

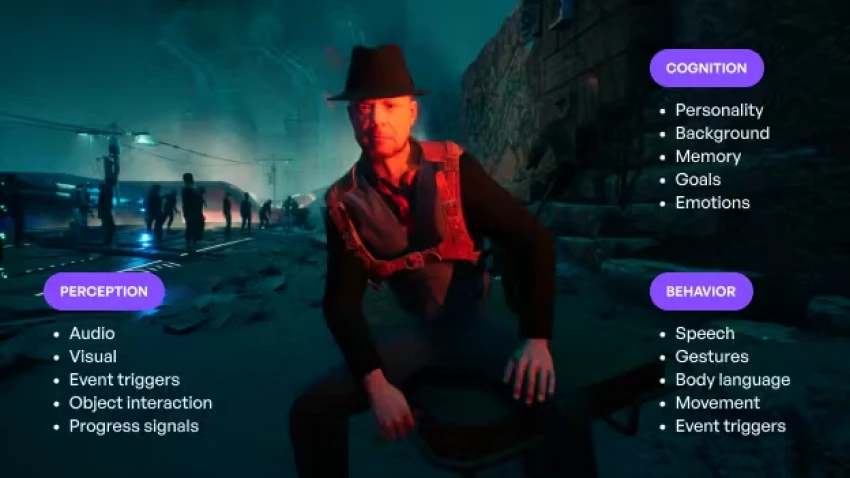

Working with Inworld feels less like using a generic chatbot API and more like wiring up a character engine plus infrastructure layer. The workflow tends to be: define a character’s personality, goals, and constraints in their studio, then hook that “brain” into your game or app via SDKs or API. It works best when you already know what role the character plays in your experience instead of “dropping AI in and seeing what happens.”

In tests, the biggest difference compared to plain LLM APIs is how conversations stay “in character” over longer sessions. Characters maintain tone and backstory reasonably well, especially in game-like contexts, although they still slip into generic AI-speak if prompts or guardrails are loose. You end up doing a lot of iteration on the character sheet and behavior settings to get them to feel consistent rather than merely “smart.”

The character brain is where most of the value sits. You can encode backstory, motivations, relationships, and “do/don’t” rules and then watch how that plays out in live conversations. In multi-character scenarios, Inworld’s multi-agent setup makes it possible for characters to talk to each other, not just to the user, which creates moments that feel closer to scripted scenes than random AI chatter.

The runtime orchestration is invisible when it works and frustrating when it doesn’t. On good days, you forget that different LLMs and tools are being called under the hood and just experience smooth dialogue. On bad days—low connectivity, misconfigured tools, misaligned prompts—you feel the chain-of-tools stack as latency spikes or odd behavior, and debugging requires understanding more of the plumbing than a simple “call GPT and reply” setup.

The TTS side is where expectations were exceeded. Voices from Inworld TTS Max sound convincingly “production-ready,” with a good balance of clarity, emotion, and natural pacing. Latency is low enough that characters can speak back in what feels like a normal conversation turn, especially on a decent connection, and this has a bigger impact on immersion than any clever prompt engineering.

Voice cloning is effective but not “fire and forget.” Short reference samples produce usable voices, but for anything that needs to carry a show, you still iterate on style and emotion tags. Compared with other TTS services, the practical difference is cost and integration: once a character is set up, tying their voice to their personality and memory inside Inworld’s runtime reduces glue work you’d otherwise do manually.

The Unity/Unreal SDKs are functional rather than delightful. If you’re used to modern game tooling, you won’t feel lost, but you also won’t call them “plug-and-play.” Expect to spend time on the integration layer: mapping character responses into in-game actions, handling edge cases when AI fails, and designing fallback states so a broken API call doesn’t break your scene.

The studio UI is clearly built for writers and designers, not just engineers, which helps in cross-functional teams. That said, if you don’t have someone thinking seriously about narrative design, motivation, and constraints, the extra knobs can feel overwhelming instead of empowering.

Inworld makes more sense as infrastructure for:

● NPCs in games and interactive stories, where personality, memory, and voice all matter more than strict factual accuracy.

● Realtime voice agents that need to sound human and respond quickly—language learning companions, coaching bots, or “sidekick” style co‑pilots.

It is less convincing as a drop-in solution for:

● Rigid, workflow-heavy customer support, where you need exact policy compliance, deep CRM wiring, and predictable responses.

● Super-simple bots or landing-page chat widgets; the overhead of Inworld’s stack is overkill for that.

In other words, it is a specialist tool: if your product lives or dies on character quality and voice, it’s worth the complexity; if you just need “some AI,” it probably isn’t.

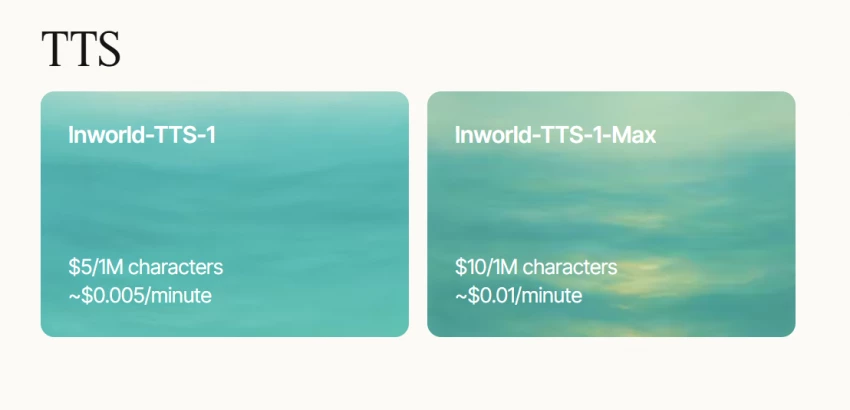

TTS pricing is surprisingly reasonable in isolation. Per-character costs for Inworld TTS often come out significantly cheaper than name‑brand competitors like ElevenLabs, which makes it attractive for high-volume voice usage. If you treat Inworld purely as a TTS backend, it looks like a bargain.

The catch shows up when you scale characters and sessions. Usage-based pricing on the character/runtime side means a successful app—lots of talkative users, long sessions can become an expensive success story. Forecasting cost is tricky: you can ballpark, but real-world conversation patterns rarely match the model you used in a spreadsheet.

For smaller teams and indie projects, the feeling is: great for prototypes and controlled pilots, but nerve-wracking if your whole game relies on it and suddenly finds traction. For well-funded companies, the concern is less about raw price and more about the combination of cost + lock-in—moving away later is non-trivial once your core experience depends on Inworld’s runtime.

Inworld presents itself like a company that expects to be scrutinized by enterprises and regulators, and the documentation reflects that. There is clear messaging around SOC 2, HIPAA, and GDPR compliance, plus a general “build with confidence” narrative aimed at risk-averse teams. From a user’s standpoint, that doesn’t change your daily workflow, but it does affect whether a security or legal team will sign off.

The platform’s governance documentation talks a lot about transparency, testing, and oversight, especially for higher-risk AI uses. However, you still have to design your own safety rails—disallowed topics, escalation paths, and high-level policies—rather than assuming the platform will enforce everything you need out of the box. Data usage is described in typical SaaS language: de-identified data for analytics and system improvement, with privacy commitments that are familiar if you’ve used other enterprise AI tools.

When everything is configured correctly, performance is the part that feels closest to “infrastructure-grade.” Latency is low enough that you can build experiences where players talk to characters as if they were other players, without awkward waiting gaps. The TTS side has been consistently solid: stable streaming, natural voice output, and minimal artifacts even under heavier load.

Character behavior is more variable because it sits on top of LLMs and prompts. Long sessions can still drift; characters occasionally break persona or hallucinate details outside their constraints. The platform gives you tools to tighten this, but it’s an ongoing tuning exercise rather than a one-time setup.

The mental model that fits best is: Inworld gives you a high-performance stage and sound system, but you still have to direct the actors. When teams forget that, they tend to blame the tool for what is really a design problem.

Public sentiment around Inworld is mostly positive, especially where people care about voice quality and immersive NPCs. Ratings on product-focused platforms skew high, with many reviews specifically calling out the TTS and character realism.

Editorial reviews and analysis sites often describe it as a leading option for AI NPCs and realtime interaction, with caveats about cost and complexity.

The pushback is most visible in game-dev and technical communities. Some developers explicitly say they would not put core game logic on a third-party AI service, citing long-term cost and control. Others find the learning curve steep if they don’t already have solid AI or narrative design skills. That split is important: teams that invest in design and infrastructure tend to report much better outcomes than teams that expect an instant “AI NPCs” button.

From actual usage and comparison work, the closest alternatives tend to fall into three buckets.

● Convai focuses more on tying AI dialogue to in‑game actions and events. If you’re obsessed with characters triggering doors, missions, or level changes from conversation, Convai often comes up as a strong alternative.

● ElevenLabs is still the “default” for many people when they think high-end TTS and voice cloning. It has a broader ecosystem around dubbing, content creation, and audio tools, and an enormous voice marketplace.

Business/support agents

● Tools like eesel AI and other support-focused platforms make more sense if your priority is ticket deflection, knowledge base integration, or CRM workflows rather than emotional, improvisational characters. Inworld can do support-like roles, but it always feels like you’re repurposing a character engine for a call-center job.

Used seriously, Inworld AI is not just another API you hit for responses; it becomes part of your product’s identity. That is both the opportunity and the risk. When the experience depends on characters feeling alive and sounding convincing, it earns its keep—particularly because the TTS quality and latency are hard to replicate on your own stack at a similar cost.

However, the tool demands clarity: clear use cases, clear cost boundaries, and clear ownership of narrative and safety. Without that, you can end up with expensive, inconsistent characters that neither your users nor your finance team will be happy with. For teams willing to treat it as core infrastructure and invest in the craft around it, Inworld justifies the effort. For everyone else, a simpler LLM + generic TTS combo is often enough.

Be the first to post comment!